Why a feature film isn’t secretly a 60-episode vertical short drama?

Every few months someone says, “A 90-minute movie is basically sixty 90-second episodes. Just cut it up.” The math is tidy. The…

Every few months someone says, “A 90-minute movie is basically sixty 90-second episodes. Just cut it up.” The math is tidy. The storytelling isn’t.

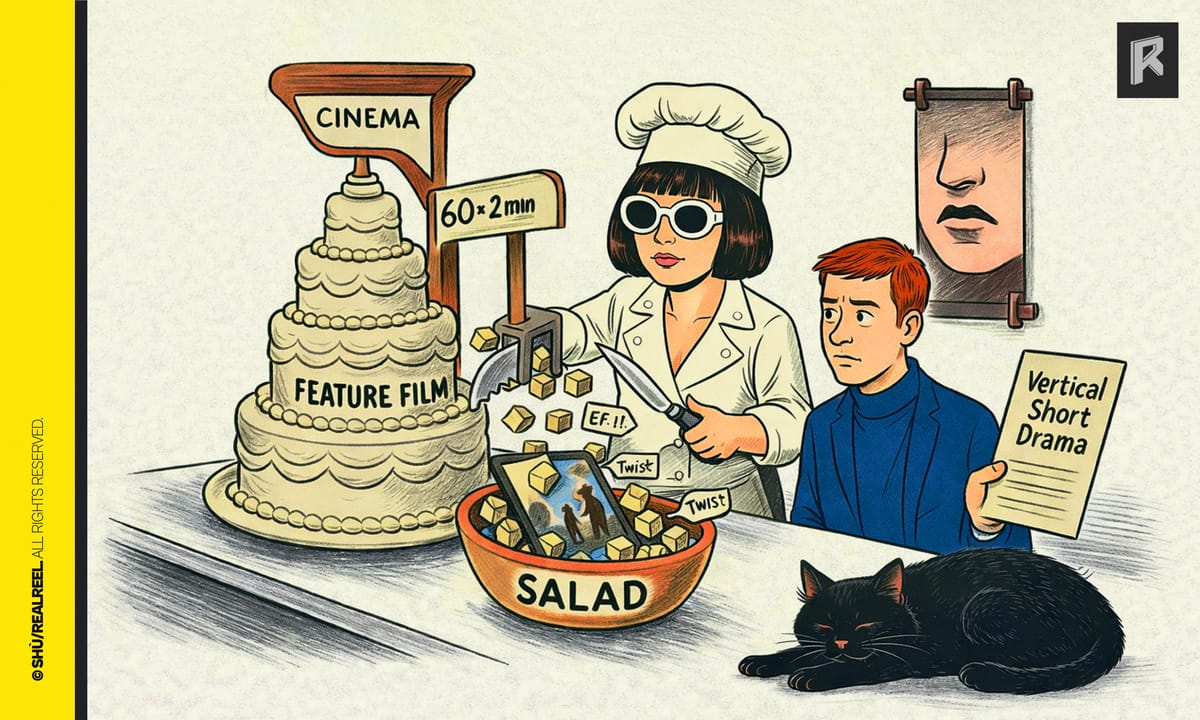

The problem is the unit of meaning. A movie is built from scenes that serve the whole; a vertical short drama is built from micro-episodes that must stand alone: each with a cold hook, a burst of friction, a payoff or reversal, and a button that dares you to tap “next.” Cutting scenes ≠ creating episodes. It’s like slicing a wedding cake into croutons and calling it a salad.

Think about a quiet scene you love. In The Godfather, the garden with the grandfather and the child is gentle, inevitable, earned by everything that came before. Now imagine it as “Episode 17,” stripped of the prior hour of moral weather. Without context, it’s just an old man in a garden. Swipe.

Scene vs. episode: different jobs

A scene can be pure setup, a shade of character, a breath that lets the audience lean in. It borrows meaning from what sits around it.

A vertical episode has to manufacture its own meaning in under a minute. It can’t assume yesterday’s investment or tomorrow’s patience. It’s a tiny engine that must start cold and rev hot NOW.

Tempo and information: the fatal mismatch

Feature films can afford to whisper. They create pressure with silence, subtext, and the dignity of time. Today’s vertical short drama can’t afford to whisper; it lives or dies by immediate stakes. Viewers make stay/leave decisions in seconds, and the format is honest about that: show me tension, a desire line, a countdown, a secret right away or I’ll scroll.

Movies also plant information to bloom later. Vertical drama mostly pays information in the moment. Every beat is a transaction: I give you ten seconds; you give me a reversal or a sharper dilemma. Repeat.

The eyeball economy (and why vertical “feels” different)

Vertical drama is the child of the attention economy. The 9:16 frame is a spotlight, not a landscape. Attention defaults to faces and the single salient point in the frame: the tell, the tear, the smirk, the slap, the reveal text in someone’s hand. In widescreen cinema, meaning often lives across the frame: foreground vs. background, left/right power, negative space, geography. In vertical, meaning collapses inward. The actor (and whatever they’re holding or doing) becomes the primary canvas; production design and spatial choreography move to the background.

That shift is more than aesthetics, it’s power. In a wide frame, status can be staged with distance and architecture. In a tall frame, status is mostly performed: who occupies the center, who owns the eye line, whose face carries the moment. Vertical “equalizes” the image by flattening the world and privileging the person. The camera doesn’t say “look at the palace”; it says “look at the prince’s mouth as he lies.”

Why “scene-slicing” breaks even when you pick the loud bits

If you cut only the action spikes: the slap, the chase, the reveal, you get pure stimulus with no consequence. If you cut only the talky bits, you get air. Either way, the emotional current that a feature spends 30, 60, 90 minutes charging never quite arrives in a one-minute window. You’re left with shards that glitter but don’t cut.

A feature can be chopped; a short drama must be engineered. The medium isn’t a “short version of a movie.” It’s a different medium built for direct, high-frequency emotional payoffs.

Next week, we’ll stop arguing against scissors and show how to rebuild a feature so it actually sings in 9:16.