Vertical Short Drama Writing Advanced 1

Maxing Out the “Satisfaction Ceiling”: Villains, the Addictive Loop, and “Useful Uselessness”

Maxing Out the “Satisfaction Ceiling”: Villains, the Addictive Loop, and “Useful Uselessness”

This is our fifth craft piece, so we’re skipping the basics. No primers on hooks or twists. We’ll focus on three advanced levers you can apply in your next 90-second episode: (1) villains that raise the audience’s satisfaction ceiling, (2) the psychological engine behind “I can’t stop watching,” and (3) the kind of “useless” details that actually make characters feel alive.

The Villain Sets the Ceiling for “How Good It Feels”

Half of the audience emotion comes from caring about the lead. The other half comes from hating the antagonist. If the hate doesn’t land, neither will the payoff.

Step 1: Tag a moral flaw immediately

Don’t over-explain motives. First, hit a common moral red flag the audience recognizes on sight:

- Relationships: cheating, gaslighting, coercion, neglect.

- Work/Society: exploitation, bullying service workers, bribery, academic fraud.

- Family: controlling a partner or child, blatant favoritism, endangering safety.

Example: At a gala, the antagonist snaps at a server and refuses a tip “Consider this practice.” One beat and we know who they are.

Step 2: Pick a cruelty style, then counterbalance it

- Blunt-force (overt): open humiliation, loud, public, undeniable. Line pattern: “You? Negotiate with me?”

- Sugar-coated (covert): “I’m only trying to help,” but every move cuts deeper. Line pattern: “If you’re uncomfortable, we don’t have to… I just want everyone happy.”

Best practice: Run overt pressure + covert needling in the same episode. One crushes from the front; the other salts the wound from the side. The lead’s situation feels tighter, and viewers burn to see justice delivered.

Quick audit for your draft

- Does the antagonist have a visible moral red flag in their first scene?

- Is their cruelty style (overt or covert) clear — and is there a counterforce pushing the other way?

- Did you avoid long speeches justifying the villain? (Explanations dilute hate.)

The “Can’t-Stop” Engine: Build the Addictive Loop

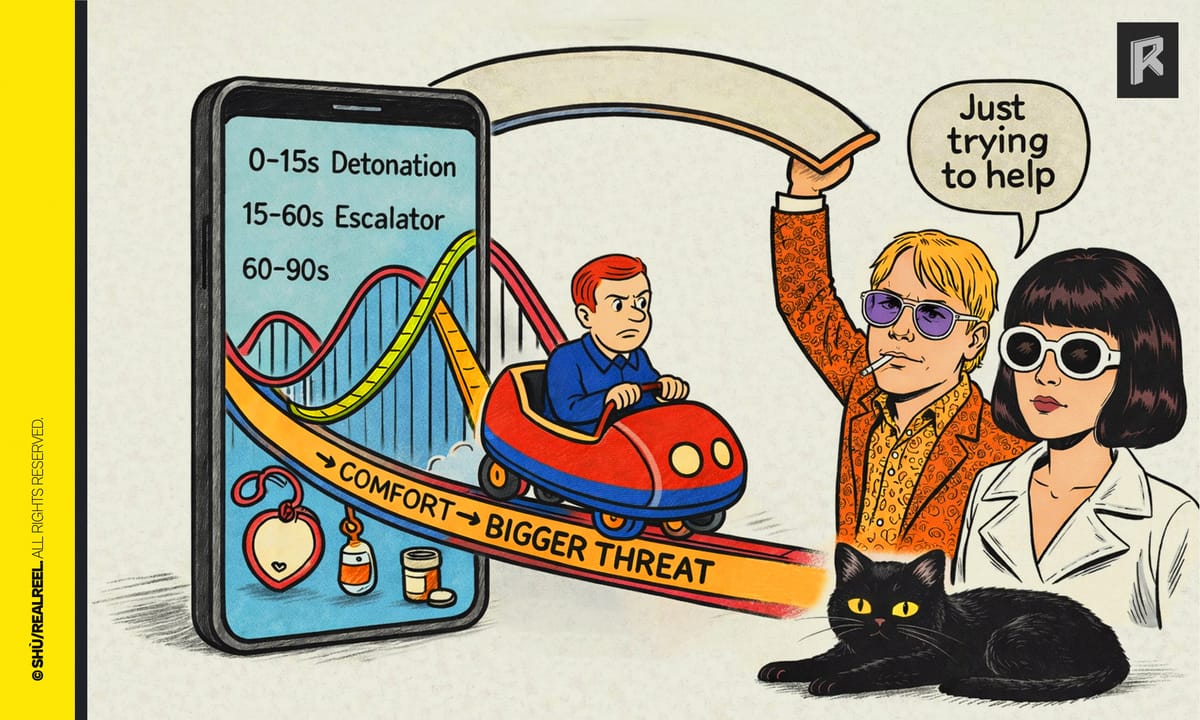

What people call “being hooked” often follows a simple loop: harm → comfort → bigger threat. It mirrors how intermittent rewards lock attention.

- Psych side (in plain English): Power imbalance + unpredictable crumbs of warmth keep attention stuck more than constant kindness ever could.

- Bio side: High stress spikes cortisol; a tiny, unexpected kindness releases dopamine; the brain overvalues that relief and wants more.

Turn it into a 90-second story loop

- Harm: public humiliation, resource loss, relationship threat.

- Comfort: one small act that feels true (a quiet “I’ve got you,” a subtle shield).

- Bigger threat: stakes or timer escalate.

Example: Boss trashes the lead in front of the team (harm) → quietly hands back the draft, “Fix this before he sees it again” (comfort) → that night, a layoff list drops with a 12-hour clock (bigger threat).

Important: Don’t romanticize abuse. Give your lead boundaries and tactical growth, even tiny, clever moves, so the loop fuels hope, not nihilism.

“Useful Uselessness”: Details That Make People Feel Real

Not every “off-topic” line or prop should be cut. Three kinds of “useless” details are secretly high-value:

Objects that speak

- Pattern: Object + where it came from + emotional contrast.

- Why it works: “Evidence” beats declarations.

Example: A rear-view charm from an ex labeled “my favorite.” One glance says more than “I loved her for eight years.”

A professional aside = antagonist’s glow-up

- Give the “bad guy” one unexpectedly expert line. It lifts the character from cartoon to worthy opponent.

Example: A racer-villain mutters, “If someone overtakes our team on this road, that’s a once-in-a-decade driver.” Instant respect, bigger world.

A past slice that powers the present

- A short, sharp flash (3–5 seconds) of sacrifice, shame, or a broken promise explains why the lead can go that far today.

Example: Quick cuts from thriving professional → reimbursed housewife — no VO, just images. Suddenly her “extreme” choice reads inevitable.

Rule of thumb: Cut explanations. Keep evidence. Less slogan, more proof.

To reliably “print” emotional payoffs each episode, fuse these three levers:

a ruthless, readable villain, the harm-comfort-threat loop, and evidence-style details that make people feel real. Start with the next scene and remember: cut explanations, keep proof.