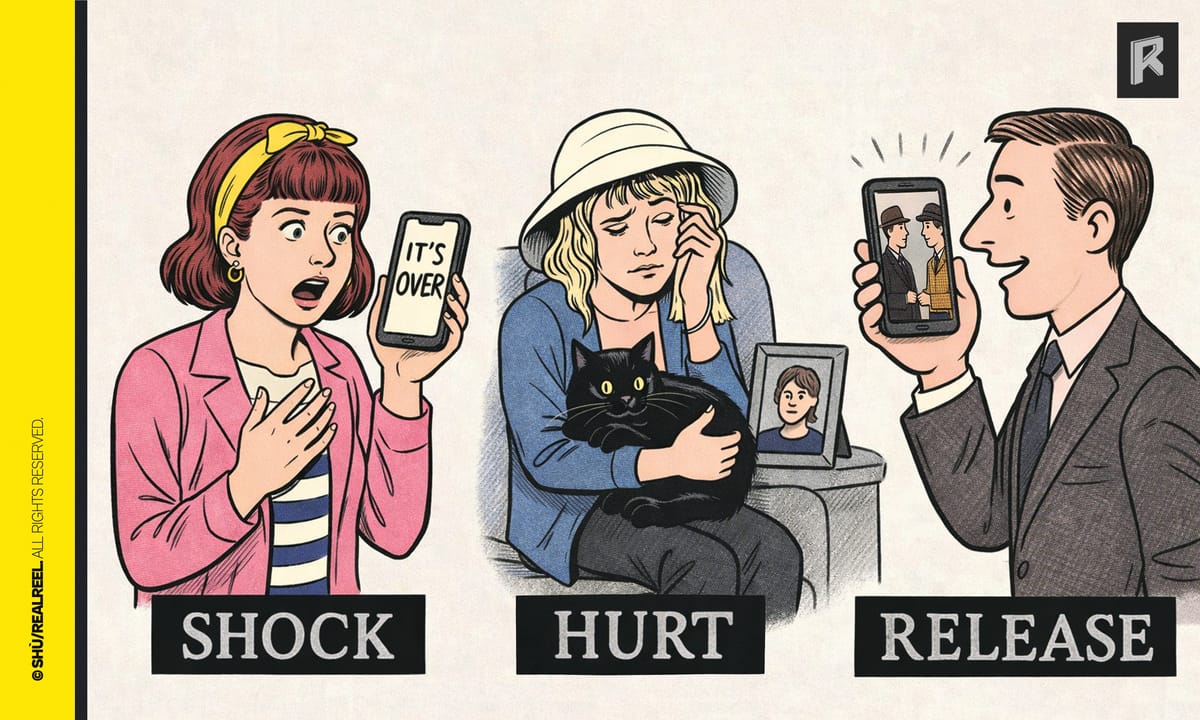

Shock, Hurt, Release: Designing Emotional Whiplash for 90-Second Episodes

The phone screen is small; your emotional swings can’t be. In vertical micro-drama, plot is a delivery system for three repeatable emotional beats: Shock, Hurt, and Release. Get those right and even the most “familiar” premise converts, because audiences don’t buy novelty as much as they buy feeling on demand.

The engine: emotion first, then incident

If your character is ordinary, the incident can’t be. That’s the shortcut to Shock. It doesn’t have to be high concept sci-fi; in relationship stories a single, undeniable reveal (the affair is real; the contract was a trap; the baby isn’t who we thought) will beat five minutes of exposition every time. On mobile, the opening two lines or two shots are your ad spend: spend them on a jaw-tightening turn.

Write it like this: open on an action that can’t be misread (video, text thread, voice memo, bank alert). Specificity is credibility. If the viewer can argue with your premise, you haven’t shocked, you’ve debated.

The cut that lingers: specificity is your “Hurt” amplifier

“Hurt” is not “the script says this is sad.” Hurt is detail. Numbers are cold; a detail is warm. Newsrooms know this: one pair of muddy boots can hold more grief than a casualty count. Translate that to script: the ringtone that hasn’t changed in ten years, the houseplant watered during a breakup, the contact name that still reads “husband ❤️”. You’re not reporting tragedy; you’re staging artifacts of it.

On the page: replace generalized emotion (“She’s devastated.”) with one physical action and one sensory cue that proves devastation without the word. Vertical framing loves hands, eyes, screens, use them.

The payback beat: earn “Release,” don’t dump it

“Release” is the high-voltage payoff: justice served, mask torn, status flipped. The mistake is front-loading gratification. If the slap lands in minute one, you’ve cut the fuse on your finale. Instead, stack friction: a near-win that slips, a public cornering, and then the mic-drop. The math is simple: accumulated injustice × publicness of the reversal = intensity of Release.

On structure: design small wins (audience hope), then bigger losses (audience anger), then the visible reversal (audience relief + triumph). Private victories are nice; public receipts are better.

Craft moves that travel

- Make the Shock visible. Texts, receipts, video, location pings — mobile-native evidence.

- Load the Hurt with artifacts. Objects + routines beat monologues in 9:16.

- Time your Release for witnesses. The more people in-story who see the reversal, the better the audience feels seeing it.

Common failure modes (and quick fixes)

- Vague openings (“a bad feeling”). → Replace with proof the viewer can screenshot.

- Melodrama without texture. → Add one concrete, repeatable behavior (she still sets two plates at dinner).

- Instant gratification. → Defer the clean win; give a partial Release and escalate stakes.

A micro-worksheet you can actually use today

When you outline, list one sentence for each:

- Shock: What can’t be argued with in shot one?

- Hurt: Which artifact (object/gesture/screen) makes the loss sting?

- Release: What’s the public act that flips status, and who’s watching?

If you can’t answer all three, you don’t have an episode; you have a premise.

Takeaway: Vertical Short Drama isn’t about reinventing story; it’s about compressing emotional physics. Build each episode on Shock, deepen with Hurt, and cash out with Release: repeat, escalate, and your “familiar” will feel addictive.