EVNT. |Going Vertical @ UCLA: Panel Lifts the Hood on the Business of Vertical Dramas

⦿⦿

Going Vertical, co-hosted by Real Reel™, the UCLA Center for Chinese Studies and the International Short Drama Association,

brought students, executives and working filmmakers into a room usually reserved for more traditional scholarship.

Join Real Reel

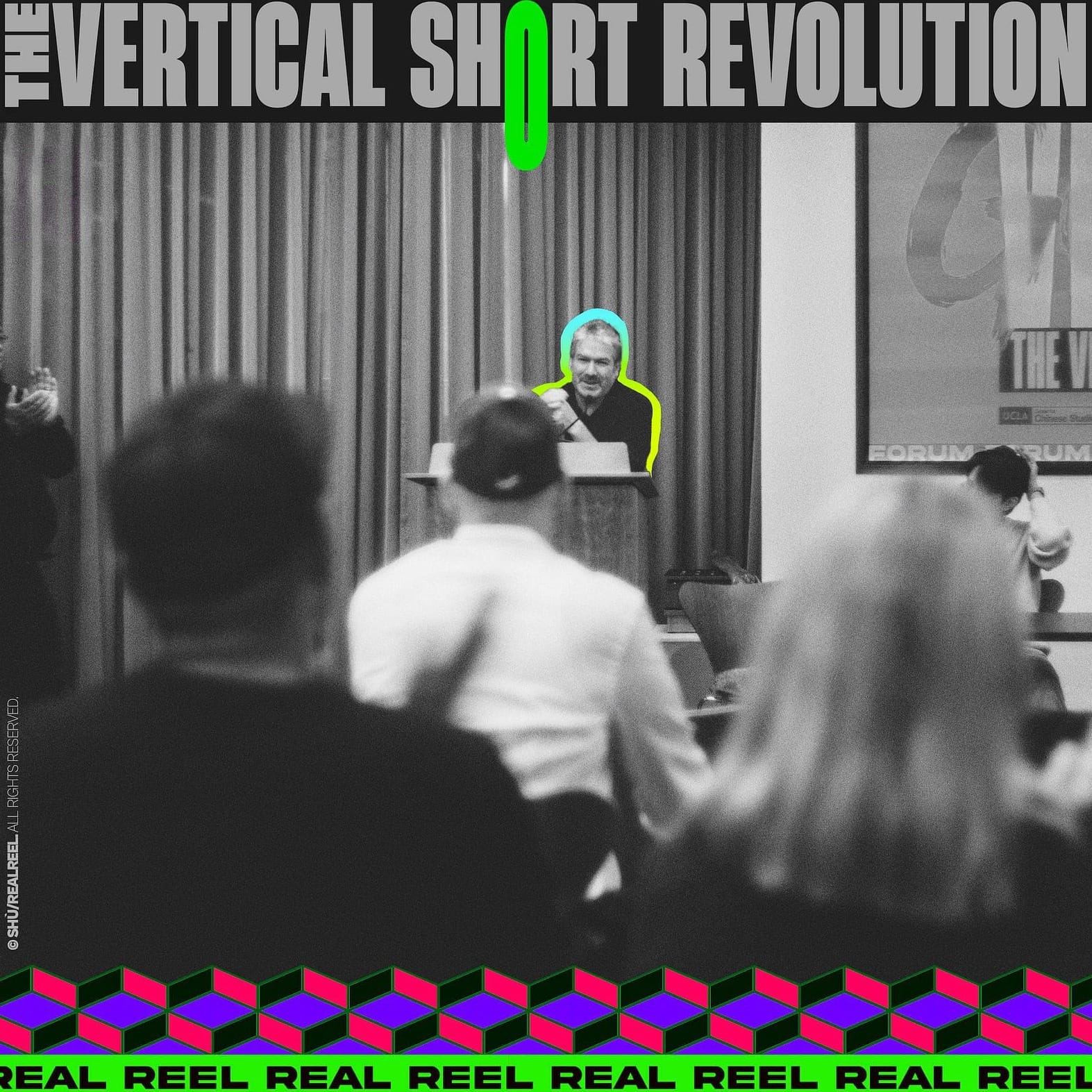

The day opened with brief remarks from Professor Michael Berry,

director of the UCLA Center for Chinese Studies, who introduced the Center’s work, thanked the UCLA East Asian Library for hosting the event, and framed the forum as part of an ongoing effort to connect campus scholarship with fast-evolving screen industries. Over two panels, the event traced how vertical short dramas are now financed, produced and shaped: both by data and by the people behind the camera.

PANEL 1 | Industry & Operations

Moderated by producer and Real Reel co-founder Celine Zen,

the first panel tackled the business side: why a 70-episode billionaire soap on a phone can out-earn a small indie feature.

Onstage with Celine were James Chen (independent producer; early team member at Playlet), Brandan Dennehy (veteran film/TV producer turned vertical strategist) and Weina Gao (producer/distributor with RealTree).

James opened with the early-startup version of vertical drama. When he joined Playlet, the “global operation” was four people: the founder, an assistant, one writer and James. On day one he was handed ten scripts: romance, workplace, women’s stories, and told to make all of them. There was no time for a long development slate. The plan was to produce quickly, launch on the app and let the audience decide. One romantic series directed by Sining Xiang quickly emerged as a major hit and quietly reset the internal rulebook.

“Data doesn’t lie,” James said. “Whatever the data loves, we make more of that.”

He noted that Playlet, like many early entrants, leaned heavily on China’s head start: drawing from existing Chinese web fiction and short dramas, then hiring U.S. writers to adapt them for local viewers. The emotional engines: CEO fantasies, revenge arcs, fake marriages, remained, but character, setting and tone were recalibrated for American sensibilities. That cross-border IP pipeline became a through line for the rest of the panel.

Brandan picked up the story from the other side of the fence. After about two decades in traditional film and TV, he joined a U.S. audio-series startup focused on high-end storytelling. Then apps like ReelShort accelerated, Chinese teams began shooting in Los Angeles and Dallas, and the company pivoted to build its own vertical drama pipeline.

The initial playbook: license popular Chinese online fiction, localize it, and build vertical shows around those narratives. The learning curve was steep: Chinese partners thought in 200-episode seasons, while U.S. production realities often meant 60–70 episodes for similar budgets, but the model gradually settled. Open the major apps today and you see the result: clusters of urban romance and melodrama built around specific, highly responsive tropes.

“There’s clearly an audience with a very strong appetite for very specific things,” Brandan said. “You can call it repetitive, or you can call it a business model.”

When Celine turned the conversation to money, James laid out the now-familiar “freemium” path. Early episodes, often five to ten, are free. From there, viewers decide whether to pay per episode or bundle, subscribe on a weekly or monthly basis, or watch ads to unlock new chapters. Inside the dashboard, revenue is tracked across three streams: subscriptions, in-app purchases and in-app advertising. In the early days, he said, ads accounted for as much as 80% of revenue; now the mix is more balanced between advertising, purchases and subscriptions.

A single breakout can underwrite a slate. The Double Life of My Billionaire Husband, Sining’s breakout hit for ReelShort with roughly 498.8 million views, was cited as the kind of series whose performance can help fund new experiments around it.

Brandan was less interested in the exact split than in how this model shapes content. To support sustained spending on Meta ads and user acquisition, the show at the center needs to be instantly legible and emotionally high-impact. “You need a story you can understand in three seconds, that looks compelling in thirty seconds and delivers strong emotional beats every minute,” he said. Right now, he added, urban romance happens to fit those requirements very well, though platforms are actively exploring additional genres.

Weina then brought in the distribution vantage point. Working with RealTree, she focuses less on what happens inside the app and more on the crucial first 24–48 hours outside it.

“Day One determines the fate of a show,” she said. “Launching the show is only its first life. Day One is when the show truly comes alive.”

RealTree coordinates launches across a large social footprint: Facebook pages reaching over 100 million followers, thousands of distribution creators and TikTok influencers, and synchronized drops on TikTok, Facebook and YouTube. Instead of relying only on traditional trailers, her team favors reaction clips, emotionally charged moments and hook-driven edits designed both to entertain and to move viewers directly into the app. Early completion of Episodes 1–3 and conversion from free to paid or ad-supported viewing are watched closely.

In the Q&A, one audience member asked whether a 20-minute festival short could simply be cut into six parts and repackaged as a vertical series. Brandan’s answer: it can be tried, but vertical is “a format, not just a frame.” In his view, each 60–90 second episode needs its own hook and forward pull, the way a half-hour sitcom or hour-long drama has its own structure. Material created originally for another format often needs its beats rethought, not just its aspect ratio changed.

Another question, whether U.S. and Chinese users behave very differently, drew a more surprising answer: within this romance-heavy lane, Brandan said, behavior looks remarkably similar. The bigger differences show up between platforms: Meta properties often convert views to paying users more efficiently than other social channels, even when those channels deliver higher raw view counts.

Panel 1 left little doubt: vertical drama is no longer a fringe experiment. It’s a functioning system built on cross-border IP, U.S. creative labor, mobile-native monetization and carefully engineered launches. For creators, the message was clear: turning the camera upright is the easy part; the real challenge is writing and producing for a format that starts measuring your choices the moment someone’s thumb pauses on your first frame.

PANEL 2 | Creation & Aesthetics

If Panel 1 mapped the business, Panel 2 zoomed in on the set:

what it takes to actually make these shows, and how the format is reshaping craft.

Chaired by Professor George Huang of UCLA TFT, the second panel brought together director Sining Xiang (The Double Life of My Billionaire Husband, Married at First Sight), veteran editor-director Shawn Chou, executive producer Johnny Jiang (NetShort) and director-producer Darren Tian (Salty TV). A writer-director and long-time faculty member in UCLA’s School of Theater, Film and Television, George has mentored generations of filmmakers on story, structure and the changing business of screen media, and he framed the conversation as a rare chance to “look under the hood” of vertical storytelling.

Sining told the story of how he “fell into” vertical. A UCLA film graduate, he left school in 2020 into a pandemic freeze, made a living as an editor and kept sending his thesis short to festivals. At a friend’s birthday party, a producer mentioned she was doing a vertical series for an app he didn’t know. He applied with his thesis as a sample and soon found himself directing The Double Life of My Billionaire Husband for ReelShort, which has since drawn around 498.8 million views.

The series was shot in April 2023, released later that summer, and slowly snowballed into one of the platform’s signature titles. Sining followed it with Married at First Sight, which has racked up about 214.7 million views, and has been growing with vertical as an industry ever since.

“I’ve been growing with vertical as an industry,” he told the room. “The process is very familiar, and then very not.”

From his perspective, much of the process is recognizably “film school” but run at higher speed. There are still four weeks of prep, visual lookbooks, floor plans, blocking diagrams, shot lists and department presentations; many of his collaborators are film-school graduates. What changes is the tempo: scripts are long, schedules compressed, and days frequently run 11–12 pages, sometimes more when locations are grouped. As platforms ask for bigger set pieces: underwater scenes, helicopters, large weddings with action… Sining has increasingly had to negotiate extra days and resources to make sure the scale on the page is matched by what ends up on screen.

Over time, he has also gained more input on the scripts themselves. Many originate from Chinese verticals; Sining now builds in a localization pass with a trusted writer to refine dialogue and add the humor and character moments he values, while keeping the underlying structure that has already tested well.

If Sining embodied the “vertical-native” director path, Shawn drew parallels from long-form television. With two decades of experience editing series like The Apprentice and Survivor, he pointed out that the idea of a constant hook is familiar territory.

“On TV, every commercial break is a cliffhanger,” he said. “You’re constantly holding onto curiosity so they don’t change the channel.”

He walked the audience through how even a polite panel could be cut into a reality-show beat, just by juxtaposing shots and a well-placed interview line. The joke landed, but so did the craft point: vertical’s rapid-fire rhythm, mini-cliffhangers every minute, not just every act, evolves from techniques television has refined for decades. The difference is that on a phone, the “other channel” is every other app on the screen.

Johnny, who has worked at ShortMax, DreameShort and now NetShort, offered a view across several company playbooks. At ShortMax, he said, in-house writers drove development; producers like him connected those scripts to U.S. production teams and weighed in on treatments and visual approaches. At DreameShort, producers became the central creative hub, sometimes writing themselves or commissioning work, which gave flexibility but meant some scripts waited longer for production.

NetShort, where he is now, reflects what has become a common model: adapting Chinese vertical hits into English-language series, shot with U.S. or U.S.-facing casts, with local teams helping refine cultural details. That can mean anything from reimagining genre elements to flying American actors to Chinese sets so performance and language land correctly for global audiences.

“In film school, the first thing we learn is ‘show, don’t tell,’” he said. “In verticals, it’s almost the opposite.”

Johnny also noted a key shift in storytelling philosophy. Scripts lean into clear dialogue and on-screen text so that viewers can follow the story even while multitasking. He compared it to a low-friction mobile experience: something people can dip in and out of easily, but that still rewards attention.

Looking ahead, Johnny sees a split ecosystem: shorter, cost-efficient series designed for volume and testing; and fewer, higher-budget verticals that push into more action and genre territory, especially as platforms court male audiences. His recent project 30 Years Frozen, Three Brothers Regret, developed with relatively light oversight, became a surprise hit and, in his view, showed that there is still meaningful creative space inside the system, even as companies continue to learn which elements can and cannot be repeated.

On NetShort, the U.S. cut of 30 Years Frozen, Three Brothers Regret didn’t just travel, it dominated: the title ranked №1 by popularity on NetShort’s July 2025 chart, generated a 1.71M “heat index” and helped the app itself climb into the global top ten, while DataEye’s international rankings kept the franchise on its global short-drama chart for two consecutive months.

Darren approached the format through analogy. Coming from narrative and commercial directing, he admitted that stepping into vertical felt like stepping into a very fast-moving experiment. One of his first questions was about audience: early conversations emphasized middle-aged women in the Midwest; later, others stressed Gen Z. A quick poll of the UCLA room: very few students had watched a full series, confirmed for him that vertical is still in the process of defining who it serves and how.

For Darren, “adaptation” is the central theme. At the story level, he argued, adaptation means going beyond translation to open up new genres and perspectives. At the talent level, it means international teams and U.S. crews learning from each other as they collaborate on projects meant for global platforms. And at the format level, it means acknowledging that the phone is simply the latest step in a long evolution from silent film to sound, black-and-white to color, theaters to television, television to streaming.

“No one expects a newborn to be perfect on day one,” he said. Vertical drama, in his view, is that newborn. “It’s our job to teach it to walk, to dance, to sing.”

Data, inevitably, was part of the craft discussion as well. Platforms share performance metrics freely; directors and producers see completion curves, drop-off points and which moments are being replayed or clipped. Sining mentioned receiving notes about lighting and specific shots that were thought to have helped a show travel particularly well. He also pointed out that, while analytics are invaluable, creative teams still rely on their own judgement about which stories they want to tell and how far they want to push certain tropes.

Taken together, the two panels at “Going Vertical” painted a picture of a medium that is both highly systematized and still flexible. On one side, there is a clear industrial logic: cross-border IP, mobile-first monetization, Day-One launch strategies.

On the other, there is an emerging language of performance, pacing and visual design that directors, editors and producers are actively shaping.

For creators in the room, and for the platforms watching, vertical drama emerged not as a finished product, but as a live, evolving format.

The infrastructure is already very real.

What it looks and feels like five years from now will depend on who chooses to step into that 9:16 frame next.