Playbook: Vertical-era characters advanced

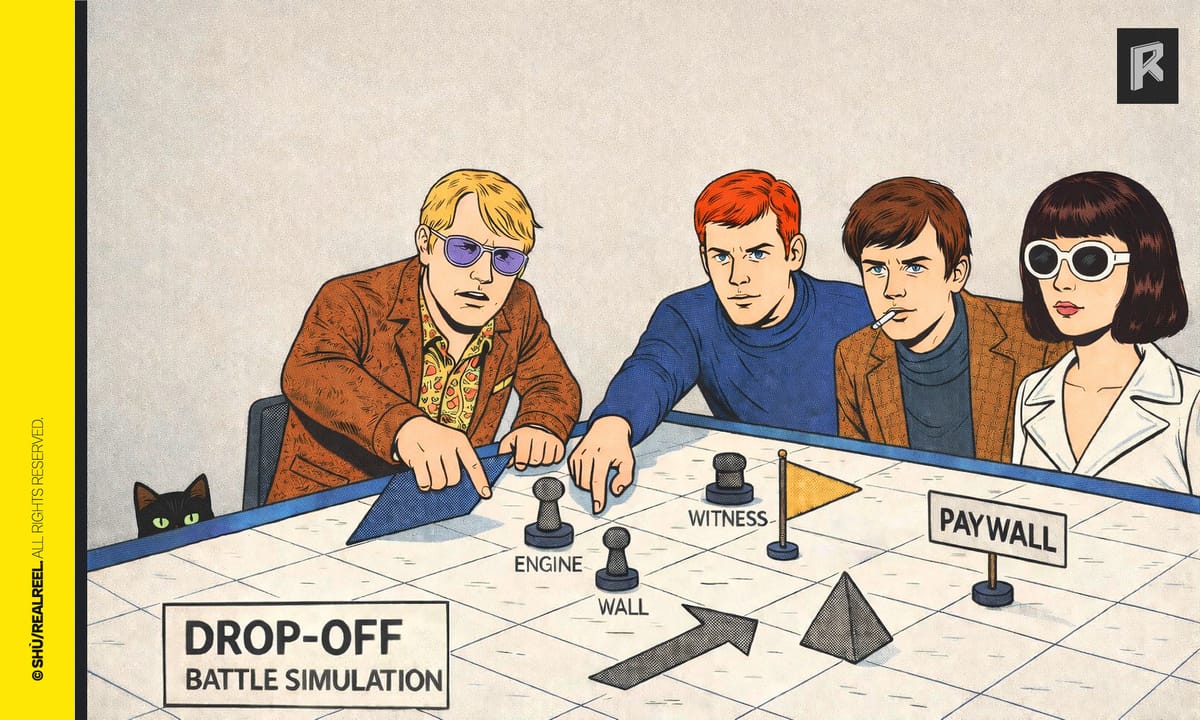

Engine, Wall, Witness, Nuke , on an actual phone screen

If you skim the current winners’ circle: How to Tame a Silver Fox, Pregnant with Billionaire’s Twins, Love Begins, Girls Help Girls: Divorce or Die, The Divorced Billionaire Heiress, Miss You After Goodbye… it’s not hard to see the pattern.

Every loop is some combination of:

- one person who moves the mess,

- one who prices the mess,

- one who speaks for the audience,

- and one truth that keeps almost blowing the mess up.

Call them Engine, Wall, Witness, Nuke. This isn’t a new “system.” It’s just a cleaner way to see what’s already working.

Engine: the thumb-mover

In vertical, the Engine is not “the lead.” It’s whoever keeps giving you new episodes to shoot.

Harper in How to Tame a Silver Fox is textbook: she chooses the club, pushes the dare, walks into the wrong man’s apartment. If she goes home early, ReelShort doesn’t have 71 episodes and 356M watches to count.

The broke student in Pregnant with Billionaire’s Twins is doing the same job in NetShort’s world: every time she runs to the hospital, confronts her family or pushes into the CEO’s space, the loop gets a new humiliation → rescue → reward cycle to play.

On the page, Engine is simple:

- we can say, in one line, what they want badly enough to make stupid choices for;

- every 3–5 episodes, there’s at least one decision only they would make, that the story can’t walk back.

If you mute the audio and can’t tell what the Engine is trying to get, or how their choices are moving the loop, you don’t have a Playbook, you have vibes.

Wall: the price tag in human form

Walls aren’t just “strict parents” or “mean in-laws.” They are price tags with faces.

In Billionaire’s Twins, the CEO and his grandmother don’t just scold; they decide who gets money, housing, medical care, and a place in the dynasty. That’s why every scene with them feels like a deposit or a withdrawal, not just dialogue.

In Girls Help Girls: Divorce or Die, Richard and the institutions around him: the firm, the court, the church aisle, function as a Wall system: they show how expensive it is for Caroline to leave, and how satisfying it is when she starts sending the bill back.

Design-wise, a Wall should answer one blunt question:

“When this person says yes or no,

what becomes more expensive to keep wanting?”

If nothing tangible changes: no money lost, no job gone, no social position hit, you may have written a loud scene, not a Wall.

Witness: the on-screen group chat

When our reviews complain that a show feels like “swallowing glass” (Miss You After Goodbye) or a “glass-box treadmill” (The Divorced Billionaire Heiress), what’s often missing isn’t twist. It’s a Witness.

A Witness is the character who:

- sounds like the audience’s group chat,

- quietly recaps chaos for latecomers,

- gives you the meme lines and reaction shots.

Girls Help Girls has glimpses of this when Caroline names patterns instead of just enduring them — she doesn’t play the victim, she prosecutes the system.

Miss You is the opposite case study: the male lead is humiliated on loop while side characters pile on. Nobody inside the frame ever says, “You realise this is the third time you cut him off mid-sentence?” The review’s “loop of misery” language comes directly from that Witness gap.

You don’t need a clown. You need one character whose job is to:

- pick a side,

- say one clear sentence the viewer can’t un-hear,

- and give the edit a place to breathe after the slap.

If your editor keeps saying “we need air,” what they’re really asking for is a Witness shot that doesn’t exist.

Nuke: the truth that keeps almost exploding

Part 1 defined Nuke as the rare character or piece of information that re-prices everything when it drops.

In practice, vertical dramas do something more specific — and more brutal:

They keep the Nuke in the room,

and let it almost explode on repeat.

The Divorced Billionaire Heiress is built on a “misunderstandings on a conveyor belt” loop: accusation → attempted explanation → interruption → public mockery → cliffhanger → repeat. Truth is always one breath away, and almost never lands.

Miss You After Goodbye pushes that to the edge: the male lead keeps trying to say “I never betrayed you, here’s what really happened,” and the heroine plus chorus cut him off every time. The review literally calls it “a loop of misery” and “a warning flare” for the market.

Meanwhile, in The Hit List we talked about “plug-and-play nuke characters”: true heiresses, secret bosses, viral-fame fixers, who exist to drop one piece of information that blows up a feed.

The craft problem isn’t “should you tease?” Platforms have made the answer obvious. The real questions are:

- Can you name your Nuke in one sentence?

- How many “almost” beats can you justify before the audience stops believing you?

- When you finally let it land, does the board actually change: money, status, alliances, or do you quietly reset to the same loop?

Rage-only titles stretch the Nuke until it snaps. Better shows still tease, but they pay at least one explosion off in a way that can’t be walked back.

You don’t need a new bible. Before the next writers’ room or pitch, a quick label pass is enough:

- Who is the Engine, and what do they want badly enough to keep breaking the world for?

- Who is the Wall, and what are they pricing?

- Who is allowed to be the Witness, not just another pain sponge?

- What is the Nuke, and when (if ever) do you stop almost-dropping it?

If you can answer those four questions in one page, your characters are already more “vertical-ready” than half of what is topping the charts.

After that, you can bend, merge, or break the Playbooks however you like. At least you’ll know which part of the machine you’re messing with.